BULLIES

![]()

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

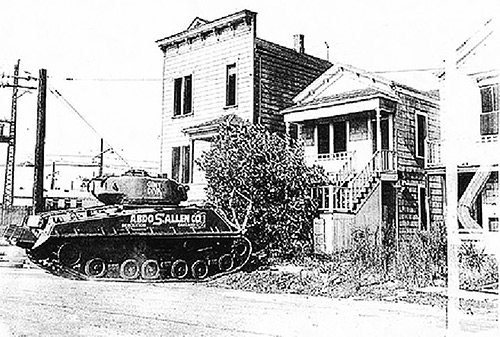

The only pictures I tacked up over my desk, or anywhere else in the house during my first year in Oakland, were old black-and-white photographs of Abdo Allen’s decommissioned Sherman tank. After a few months, I photocopied three of the photos, folded the copies up, and tucked them into my wallet. That way, if some out-of-town friend were to ask me, “How did Oakland get to be so fucked up?” I could start with some history, show them some pictures.

The question came up a lot that year, which was also the year of Cairo’s Tahrir Square and New York’s Zuccotti Park, and the first time in decades that Oakland, a working-class city on San Francisco Bay, became a fixture in the national news cycle. It was the year of Occupy Oakland, and the Black Muslim Bakery murder trials, the year that Harold Camping’s Oakland-based Family Radio ministry predicted the end of the world, twice, while Oakland’s murder rate (already one of the nation’s highest) ticked upward, and the year that the New York Times picked Oakland to be the world’s fifth most desirable place to visit (something about “upscale cocktail bars, turning once-gritty Oakland into an increasingly appealing place to be after dark”), placing it higher on the list than Glasgow, Moscow, and Florence. This was news to the city’s residents—though Oakland did have good bars, and the local cops were so overwhelmed that, if you steered clear of the highway patrol, it was almost impossible to get a DUI there. But two days later, the Times published a follow-up: “Shootings Soar in Oakland,” the headline read. “Children Often the Victims.”

“How did Oakland get to be so fucked up?”

I’d fumble around for my wallet.

The first photo I’d tucked away there was taken by an AP stringer in the summer of 1960. It showed the tank from behind as it ripped through a house in West Oakland. The second photograph showed the tank from the front, covered in the rubble of a lot it had already cleared. Both photographs looked like they could have belonged in a History Channel documentary about World War II. But the third photograph showed the tank in full profile. You could see the words “ABDO S. ALLEN Co.” hand-painted across its hull, the dust coming off of its treads, the two-story home that it was about to plow into. The home was an American home. The story this photograph told was an American story—about urban renewal, industrial decay, brute force, and bullying. But the machine was not a metaphor. In some other city—Detroit, or Baltimore, or even New York—you might have looked at a blasted-out neighborhood and thought, “It’s as if they’d driven a tank through it.” In Oakland, they had used an actual tank.

If you’ve spent any time in Oakland, there’s a good chance you’ve heard of the East Bay Rats Motorcycle Club, which has its clubhouse near the corner of Thirtieth Street and San Pablo Avenue in West Oakland.

The EBRMC is not an especially old club; the Rats formed with just a few members in 1994. But they made a quick impression, getting into barroom brawls and backroom gangbangs, and leaving tread marks—the gummy residue of burnouts, spinouts, and other cool motorcycle moves—up and down the length of San Pablo Avenue. The Rats installed a boxing ring behind their clubhouse, and hosted fight parties that drew thousands of people. They became known for their Fourth of July fireworks displays, which eclipsed Oakland’s own, and for shooting guns, smashing cars, setting motor scooters on fire, and blowing propane tanks up in public. The Rats burned sofas, old pianos—whatever they could get their hands on—out on the San Pablo median strip. Once, they’d dragged a full-size fighter jet engine out into the avenue, angled it upward, and used it to incinerate the neighborhood lampposts. And in 2001, the Rats did something that the Bay Area’s residents still haven’t forgiven them for. That summer, a gray whale beached itself on the San Francisco shoreline. “It had the shape of whale, flukes, rising backbone, long, tapering head and bird-beak upper jaw resting on the wider yoke of the lower jaw,” the journal of the California Academy of Sciences had reported. “During the night, someone had climbed on top of it and painted in large yellow letters, ‘East Bay Rats Motorcycle Club.’ ”

The Rats went on to tag more whales. They added more members and continued to attract attention. In 2005, the audience of a cable show called Only in America watched the show’s host, a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist named Charlie LeDuff, fight a three-hundred-pound Rat named Big Mike, and lose. Four years later, Gavin McInnes fought Meathead Eric in back of the clubhouse. Eric was a mixed martial artist. McInnes, a cofounder of Vice magazine, was filming the pilot for a reality show called The Immersionist. Eric beat him senseless in less time than it would have taken them to have watched a TV commercial, and The Immersionist was not picked up for distribution.

The Rats were hard to pin down, gather up, or control for any length of time. They wore black leather, broke people’s bones. They had mixed feelings about the cameras. And they’d formed in response to conditions—economic collapse, real devastation wrought by the crack epidemic—that did not fold themselves neatly into the narrative arcs of half-hour reality shows. In some strange way, the Rats were like Allen’s tank, personified and projected fifty years into the future: they did not belong on the city streets. The club would have been a natural starting point for anyone who wanted a deeper understanding of the place that tolerated, even celebrated its presence. But my interest in the EBRMC was more personal—and my interest in the club’s president, Trevor Latham, was more personal still.

CHAPTER TWO

I first met Trevor in the fourth grade, at an elementary school in Huntington Station, Long Island. I was eight, Trevor was a year older, but I still remember the way his house looked, in that first year of Ronald Reagan’s first administration: with its two unkempt stories and lawn full of weeds, it looked almost exactly like my house.

Like me, Trevor lived alone with his dad. Like my dad, Trevor’s was an aeronautics engineer in one of the nearby military-industrial mills. Our dads had both been athletes, once. In their youth, both of them had raced motorcycles. Now time had caught up with them, twisted a knife. Trevor and I felt the weight of their burdens at home and pushed our own weight around in the school yard. We were nowhere near puberty. But well into adulthood, my memories of Trevor involved punching and kicking, biting, blind fear, and sheer, animal rage.

Why did Trevor pick on me? Because I was the new kid in school—a perpetual new kid, I’d moved several times already. Or, it was because I was young for my grade and small for my age, bookish, and sad. My parents had split up a few years before then, and I’d gone to live with my mother in Pittsburgh. Then my mother died and I went to live with my father, near Boston. Then my dad lost one job, and then another, and we moved again, and again, tumbling through the American dream before ending up out on Long Island. I know now that Trevor had had his own sorrows. But back then, I was too young to register them. To me, Trevor was simply a bully: someone who would wait for me, out by the schoolhouse door every morning, and threaten me with the things he would do to me once school got out. The threats were not idle: I’d come home bruised, sometimes covered in dog shit, and if the next day was a school day, I’d wake up expecting more of the same. By the end of fourth grade, I’d begun to play hooky. By the end of fifth grade, I was flunking my classes. At the end of sixth grade, my dad and I moved yet again—a move that was followed by still other moves, until, five years later, I dropped out of high school and moved, one last time, to New York. By then my bully had turned into a shadow, and then just a name, which I’d remembered because “Trevor Latham” was such a good name for a bully. The truth is that, by our late teens, neither one of us would have recognized the other.

Decades passed. Then, one day in 2006, I came across Trevor’s alumni note (Walt Whitman High School, Class of 1990): “I moved to California, became a bouncer, and started a motorcycle club,” it read. To me, this made sense: my grade-school nemesis had become a professional bully. Nevertheless, it was startling.

Trevor’s club had a website—a no-frills affair with a splash page that read:

EAST BAY RATS MC

Support Your Local Ratbike

Clicking through, I saw scans of old fight-party flyers, advertisements for pole-dancing contests, and photographs of wild pigs, or boars, that the Rats had hunted and gutted and laid in a line. Below them, there was a photo of a man who’d posed with his back to the camera. A massive tattoo of the East Bay Rats’ logo, a stylized rat skull, took up the whole of his back. The caption read, “Trevor and his new Tattoo.” But I couldn’t see Trevor’s face in the photo, and there wasn’t that much more to go on. The Rats hosted bands at the clubhouse and charged ten dollars for boxing lessons. They sold swag—support stickers, and sweatshirts that read:

EAST BAY FIGHT NIGHT

Support Consensual Bloodshed

The website’s “buy” link still worked, but others went nowhere or led to pages that said, “Coming Soon.” But there, on the home page, I saw one more photo, of two men fighting in front of a crowd. The first man was throwing a punch—a right cross. The second man had thrown his hands up, defensively. He had dark, curly hair, a face streaked with blood, an alarmed expression. He looked, a little, like me. But it was the first man I couldn’t stop looking at. He was light-skinned and shirtless, in black jeans and boxing gloves, and he was squinting, which made it harder to make out his features. Still, the punch he was throwing was one I remembered from childhood.

Could this man have been Trevor?

I got up and went to the kitchen, where I drank one beer, and then another, and smoked the first cigarette I’d had in months. Back at my desk, I enlarged the photo, again and again, until I was staring at pixels.

I thought it was Trevor.

I couldn’t be sure.

But I felt an old shudder and knew then that I would call him, write him, or, perhaps, write about him.

That week, Trevor was all that I talked about. “You’ll have to go out there and fight him,” friends said, and I got the sense they were only half-joking. But I wore glasses, wrote book reviews then, and worked as an adjunct professor. Trevor was a biker, a bouncer, a boxing instructor. He taught where the organs were, how to hurt people.

“I’ve fought him already,” I said.

I did not want to fight him again. But I did want the story to tell. His story, mine—whatever it was that had tied us together, back then, and carried us into the now. One night, I worked up a pitch, which I sent to a friend of a friend who worked at Gentleman’s Quarterly. Then I dialed the number on Trevor’s website.

It turned out to be Trevor’s number.

He was out at a bar when I reached him. A grumble of voices crowded the line and I had a moment to wonder: would Trevor remember me now? For all I knew, he was brain-damaged, crazy—all of the fights that he’d been in, the blows to the head. I didn’t know quite what to picture or say.

“Hello?” said Trevor.

“We knew each other in grade school,” I said.

There was a pause. Then I heard my own name.

“Alex?”

“Trevor?”

“I was just talking about you,” he said. “Yesterday, telling a friend all about you. My friend told me, ‘One day, you’ll walk down some dark alley. At the end, you’ll meet Alex Abramovich.’ ”

I was taken aback. Trevor didn’t sound damaged, or crazy, or even surprised. He spoke slowly, carefully, assigning equal weight to each word.

“My friends all say I should fight you,” I told him.

“What do you think?”

“That they’re being ridiculous.”

Trevor laughed. Then he asked where I was, and I told him that I was at home, in my apartment in Queens. He asked what I did for a living. I told him that, too. Then he took down my number and said that he’d call me back after he’d closed up the bar.

He never did. I tried him again, calling and texting in the days that followed. There was no response. Then I heard from GQ and texted again: “I pitched our story to GQ,” I wrote. “They’re interested.”

This time he replied right away. “If you want to be Hunter S. Thompson about it,” said Trevor, “you can stay at the clubhouse, ride a bike, and live the life for a while.”

I told him that I’d book a ticket that night.

Copyright © 2016 by Alex Abramovich